Temple of Dionysus at Teos, 3rd century BCE

It becomes apparent in my

previous post on the sources and the chain of corrupting the Dionysiac Artists into the Dionysiac Architects is long, tedious, and repetitive, and likely needs summary. I would recommend anyone doing research into this group to refer to that post for a deeper study, but here I would like to summarize the content of that post, and to contextualize and commentate as needed to understand this group and how their image was drastically modified over the last few centuries.

The earliest sources for the Dionysiac Artists are Strabo and Aulus Gellius. Strabo describes them as something like a traveling band of entertainers, which is not that unusual of a thing, seeing as entertainment companies were known in the ancient world and continued as a tradition even up until this very day to tour and move about. There are only so many skits, poems, and musical pieces a group can perform in a town before everyone has seen it. To keep both the entertainment and the audience fresh, groups of entertainers will move from town to town throughout a region performing their usual set to a new audience every few weeks, and the town gets new entertainment every so often as well with a new group. It is a pragmatic approach to entertainment, and the fact it still works this way today should indicate that this approach is neither novel nor unreasonable. Thus, the Dionysiac Artists are not that unusual, though they may be one of the first or the most notable, though in reality they are probably only notable because anything about them survives today.

Like any band or entertainment corporation today, they are stationed somewhere. The Chautaqua Circuit of the 19th and 20th centuries was founded and stationed in Chautaqua, New York. The USO was founded and still stationed in Arlington, Virginia. The band Metallica was founded in Los Angeles, California and still largely resides there today. These are all itinerant entertainers with a home base. Likewise, the Dionysiac Artists were founded in Teos on Aegean Coast of western Turkey in the region then known as Ionia. As a travelling company of entertainers, they moved about the coast of Ionia providing entertainment in various towns. We know they went as far northwest as the Dardanelles (Hellespont), and probably went as far southeast as Ephesus or a little further. They covered an area about 400 kilometres (approx. 250 miles) based on the known locations they traveled to.

This particular group of entertainers are devotees to Dionysus, because Dionysus was the patron deity of theater and the City of Teos. The town itself was noted in its time for its theater, its wine, and its Temple of Dionysus. This appears to be more in line with the custom of groups with a patron deity, rather than that they were initiates of the cults of Dionysus. For instance, blacksmiths were usually devotees of Hephaestus, and athletes were frequently devotees of Herakles. This does not mean they were only devoted to these deities, but rather due to their vocations were especially devoted to these deities and demigods. Nor does it mean they were members of these deities' cults, though they likely would be. Further, affiliation to a cult was not as formal in antiquity as it is today, so a clear definition of "membership" is loose and vague. The Dionysiac Artists in particular were devoted to Dionysus, however the individuals may also make devotions to other deities, which was customary in Greece. The members of the groups may or may not be initiates of the Mysteries of Dionysus, and it is likely many, if not the vast majority were, but that would be on an individual basis, and likely not the requirements of the company as a whole. We do not know much of anything about their customs and regulations, so pondering these things is venturing into the realm of speculation.

According to Chandler's interpretation of Edmund Chishull's transcriptions and translations of various stone fragments found throughout Ionia (Antiquitates Asiaticae), as well as his own examination of a particular tablet (Travels), these Dionysiac Artists committed an act of sedition and failed, and were forced to relocate. According to Strabo, they relocated their home base several times. They started at Teos, moved to Ephesus after a failed act of sedition, later relocated to Myonneus by King Attalus I, and finally would settle in Lebedos.

Strabo mentions this sedition, but does not state who started it, though he appears to imply it by mentioning it in the first place. The reason for this sedition is not known, but is probably related to two completing factions in Teos at that time. Chishull mentions two organizations in Teos that appear to be at odds with each other: the Commune Attalistarum, who were aligned with King Attalus I of Pergamon, and the Commune Sodalitii ab Echino Dictii, who appear to be an allegiance of Athenians occupying Teos. Chandler in his Travels describes one of the fragments that mentions the Panathenaists and the Dionysiacs. It would appear the Dionysiac Artists were of those loyal to King Attalus I, and this is reasonable given that Attalus favored the Dionysiac Artists, and he would later give them a home at Myonneus. Given the fragments translated by Chishull, we may surmise part of the grievance of the Dionysiac Artists while in Teos is the desire to have the new governance to uphold old laws.

Much of this civic and political conflict appears to arise out of the Macedonian Wars. Philip V of Macedonia had allied with Hannibal of Carthage against the Roman Republic. During this campaign, the Aetolian League of mainland Greece would join forces with the Romans in a naval conflict to prevent the Macedonians from expanding into Anatolia, which started in Ionia. They were successful against Philip V in 215 BCE. Attalus I of Pergamon (an Ionian city) convinced the Roman army to assist in retaliation, and Philip V was ultimately defeated at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE. This guaranteed the Ionian cities to remain autonomous while under Roman rule. The Romans were heavily concerned with securing land and resources, but were not in favor of converting or micromanaging local municipalities. So while they governed a city or region, they allowed them to maintain autonomy in their own religious, political, civic, and economic matters. Since the Aetolians were involved in securing Ionia, as well as the Athenians, there was conflicts between Roman governance, Athenia and Aetolian laws, and Ionia maintaining their old laws and decrees. Let me be clear, I am greatly oversimplifying, and probably improperly overgeneralizing the events of the Macedonian Wars (and I am probably confusing some things or illustrating them improperly, but the Macedonian Wars are not something I am totally familiar with), but it is not entirely necessary to understand these. What we need to understand is that old city-states with their own allegiances and laws suddenly were in conflict with new governors and new residents, and disputes over old laws and customs needed to be addressed and honored.

Of particular importance is an old agreement that Ionia is sacred, and Teos should not be seized nor its citizens violated in any manner. Their right to asylum, sovereignty, and their right to honor Dionysus was been asked to be upheld. The Dionysiac Artists amongst the loyalists of Attalus appear to have felt an old decree was being violated by the occupying Athenians and Aetolians — if Chandler is correct in his assessment — we may surmise they committed an act or conspiracy of sedition. The fact that they had to leave Teos and relocate to Ephesus indicates that they failed in their sedition.

Further, it should not be surprising that a group of entertainers got involved in politics or even political uprisings. Entertainers usually have a public platform by the very nature of their profession, which is useful in political discourse and influence. Further, many entertainers put political and civic dissent and protest into their work. It is certainly prevalent today, and we should not expect it to be any different in antiquity. Euripides's The Bacchae is a rather political charged piece concerning the political struggles against the growing cults of Dionysus. Shakespeare's works are oftentimes very political. Even today, bands like Rage Against the Machine illustrate entertainers using their public platform to exercise political dissension. And even very recently, Jon Schaffer of the heavy metal band Iced Earth was amongst the insurrectionists that stormed the United State's Capital on January 6th, 2021. The fact the Dionysiac Artists got involved in political dissension and sedition is not that surprising when we consider the long history of entertainers' involvement in political dissent.

This illustrates that the Dionysiac Artists are not a group of exactly high morals, or at least is not above illegal schemes. Aulus Gellius illustrates that they were not exactly a positive group that should be admired. His Attic Nights is a fantastic collection of stories and personal anecdotes that is useful to historians endeavoring to understand the social context and the views of the populace of Hellenistic Greece. Aulus Gellius describes the Dionysiac Artists are being potentially corrupting to the youth, as he describes a young man who admires them. This young man is a student of Lucius Calvenus Taurus, a Middle Platonist philosopher, who tries to dissuade him by instructing him to read some of Aristotle (probably De Interpretatione). He tries to show his student that these Dionysiac Artists are intemperate (e.g. drunk, gluttonous, sexually promiscuous) and unenlightened. Their general waywardness and impoverishment is a road to wickedness. Obviously, Aulus Gellius has nothing good to say about the Dionysiac Artists. Mix this with their alleged act of sedition, and one may begin to wonder how this group was turned into a fraternity of high morals.

Two notable people are responsible for equating the Dionysiac Artists with modern day Freemasonry: John Robison and Alexander Lawrie. Robison was a Scottish physicist and lived in Edinburgh. Following the French Revolution, he became disillusioned with the Enlightenment movement, and in particular Enlightenment societies, especially the Freemasons. Thus he penned Proofs of a Conspiracy, and in the first chapter he describes the Dionysiac Artists as being an earlier precursor to Freemasonry. He is the first person to make such a claim, however he does not claim that they became the Freemasons in any sort of genealogical manner, but rather the principle of the Dionysiac Artists as a trade association is a prototype of the trade corporations of the Middle Ages, i.e. the guilds, which in turn led to the Freemasons. He does however apply a number of claims about the Dionysiac Artists that are completely unfounded, such as secret words and signs of recognition. He would then directly influence Alexander Lawrie, a Scottish Freemason also living in Edinburgh. Their close proximity to each other may be ultimately how Lawrie became aware of Robison's work, and may be the sole circumstance responsible for transforming the Dionysiac Artists into the Dionysiac Architects.

Lawrie believed everything Robsion says about the Dionysiac Artists being a precursor to the Freemasons, because Robison was an Anti-Mason, and therefore does not have any reason to lie, because he does not share the Masonic agenda. To quote:

"Dr. Robison, who will not be suspected of partiality to Free Masons, ascribes their origin to the Dionysian artists. It is impossible, indeed, for any candid enquirer to call in question their identity."

However, where Robison is careful not to assert that the Dionysiac Artists became to Freemasons, Lawrie is convinced that they did. Like Robison, Lawrie renders this mysterious organization of entertainers as plastic to make them pliable to the image he wants them to have. Lawrie sees all ancient mystery cults being more or less the same thing, and believed that any thing that was similar in nature and substance is more or less the same thing. Therefore, the Dionysiac Artists being so similar to Freemasonry — because Lawrie makes them seem similar to Freemasonry — they are therefore the same thing. To quote:

"If it be possible to prove the identity of any two societies, from the coincidence of their external forms, we are authorised to conclude, that the Fraternity of the Ionian architects, and the Fraternity of Free Masons, are exactly the same; and as the former practiced the mysteries of Bacchus and Ceres [i.e. Eleusinian Mysteries], several of which we have shown to be similar to the mysteries of Masonry; we may safely affirm, that, in their internal, as well as external procedure, the Society of Free Masons resembles the Dionysiacs of Asia Minor."

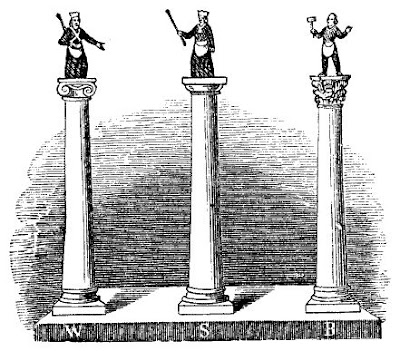

Unlike Robison, Lawrie appears to actually be familiar with the works of Richard Chandler, and probably had access to Edmund Chishull's text, though it does not appear that Lawrie knew Doric or Ionian Greek or Latin, as he pulls information from Chishull that is not in Chandler's works, but makes grave blunders that are either deliberate misrepresentations or ignorant misunderstandings; the latter seems most likely. For instance, Chishull mentions two competing factions in Teos, which Lawrie misrepresents as two lodges of the Dionysiac Artists. He takes Chandler's mentioning of a "president" of the annual festivities to mean that these lodges were governed by a master and wardens. Chishull mentions utensils and instruments concerning a damaged stone fragments, which Lawrie misrepresents as Masonic implements still in use by Masons today. One of these stone fragments Chishull translates was relocated from the Aegean Coast to central Turkey and used by the Turks as a gravestone. Lawrie misrepresents this as a monument built by the Dionysiac Architects to honor their deceased masters and wardens. Et cetera. He appears to be attempting to mold this organization into something like the funerary associations of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, which modern day Freemasonry still contains a remnant of in tending to their deceased members. Due to this sort of charity, Lawrie further adds that the "more opulent" members helped provide assistance to the "poorer brethren," which is a confabulation of Lawrie's own devising.

Lawrie may have been familiar with Strabo, but he only seems to copy the citations for Strabo given by Chandler. He does appear to be familiar with Aulus Gellius, however, he does ignore certain things Aulus Gellius tells us about the organization, namely that they were intemperate and unenlightened, as well as Chandler's conclusion that they caused the sedition in Teos, for Lawrie wishes to make them seem more like Freemasons, a fraternity of moral teachings. Further, he cites Book 8 of Attic Nights, which is the only book of this work that is lost; only the index survives. Lawrie obviously could only look at the index, as Chapter 11 mentions a Dionysiac festival, so clearly he wished this to be by the Dionysiac Artists. He cites this lost book of Attic Nights in his discussion of the different bogus lodges of the organization, making him seem even less credible.

Several things described about the Dionysiac Artists make it really easy to mold them into the image Freemasons have of their operative progenitors. Freemasons claim they come from the operative stonemason guilds of the Middle Ages and they claim the individual stonemasons were free to move about (hence Free Mason). I address this conception and the problems with it, as well as why it really is not as special as Freemasons think it is in a previous post. The fact that these Dionysiac Artists were said to have moved about, like the stonemasons were supposed to have done, is not that special. Further, their Greek name Διονυσον

τεχνιτων (Dionyson techniton) can be misconstrued. The term techneton can refer to a number of things and is usually used to designate an artisan, carpenter, builder, etc, and is the root of the word architect or "chief builder." However, techne is much more multifaceted of a term, as Martin Heidegger illustrates in his essay "The Question Concerning Technology." It concerns things such as craft, art, cunning, creating, etc. Heidegger relates techne to poesis, from which we get words like poetry, and he posits that techne is a process of revealing. In considering this, we can see how Robison misconstrues them as "undoubtedly an association of architects and engineers" and Lawrie follows by claiming they built temples and theaters. Rather than understanding techniton as a creator of entertainment, they misrepresent this multifaceted word to specifically mean an architect and builder. There are many other instances of misunderstanding or misrepresentations by Lawrie concerning Chandler's work, but we need not get into them, as they are small and, frankly difficult to figure out how Lawrie got things so wrong.

Following Lawrie by a few years, we get Hipolito Jose da Costa, who would cement the reputation of the Dionysiac Artists forever in the annals of Masonic legendry. Da Costa was a Brazilian diplomat and journalist, called by some the "Father of Brizilian Journalism" and is best known for getting arrested by the Portuguese Inquisition on the charges of being a Freemason. Where da Costa got the idea to write about the Dionysiac Artists is a bit of mystery. His citations are nearly all ancient sources, which is a bit suspicious. Even modern researchers on antiquity will cite contemporary scholars who provide meaningful insight into the ancient world. Da Costa probably wanted to present himself as an antiquarian, which would add credit to this thesis that the Dionysiac Artists were somehow Masonic in origin. However, many times his citations appear to be copied directly from Lawrie and Chandler, and since Lawrie would copy Chandler's citations, it is entirely possible da Costa came across Lawrie's text and looked no further.

Da Costa's Sketch for the History of the Dionysian Artificers: A Fragment is a disjointed mess. He, like Lawrie, wishes to present all ancient mystery cults as being more or less the same thing. Whereas Lawrie sees all ancient mystery cults as the same thing due to being rites of initiation, which Lawrie then tries to make seem Masonic in essence, da Costa sees all mystery cults of antiquity as being the same due to astrological and star lore similarities. When he gets to actually discussing the Dionysiac Artists thirty pages later, he creates arguments and makes claims none of the previous writers (Lawrie or Robison) makes. He says they were amongst the builders at Byblos and therefore were the Gebalites that Hiram King of Tyre asked to help build Solomon's Temple. Since Hiram Abif is one of the craftsmen sent by Hiram of Tyre, he therefore assumes Hiram Abif is one of the Dionysiac Artists. He claims the Dionysiac Artists introduced their mysteries into Israel. Da Costa then goes onto claim that they survived until the Crusades and then moved into Europe and the British Isles, where they became the modern Freemasons. Where he spent thirty pages trying poorly to explain how the Dionysiac Artists were part of all mystery cults, yet he only spends a page stating this with no argument for it whatsoever.

The whole text is a "scholastic" nightmare. Even Albert Mackey admits "his reasoning may not always carry conviction," albeit Mackey himself applaud's da Costa's essay as it "draws a successful parallel between the initiation into these [mysteries] and the Masonic initiation." His logic is beyond flawed, he presents terrible arguments and justifications for his claims, if he gives an argument at all, and all around it is poorly written. His citations don't actually provide material that supports his claims. It feels like da Costa had an idea that he loosely pieced together from false claims by other Freemasons he heard or read, could not remember properly what they said, and assembled a fragmentary sketch that would have been better gone unpublished and lost in some Masonic archive. But it didn't. Both Albert Mackey and Manly P. Hall would pick up this work, and Hall especially would revere this essay, as he would later republish it with his own introduction.

The next big alteration of this group of traveling, seditious, drunken entertainers is Robert Macoy, who claims they were priests of Dionysus. This contradicts the spirit of everything we know about the cults of Dionysus, namely that their members were largely women, and their hierarchy was governed by women, i.e. priestesses. One fragment discussed by Chandler in Ionian Antiquities mentions a pedestal of one of the Dionysiac priestesses named Claudia Tryphaena. Macoy does not give the sources of his information, but based on the claims he makes in his encyclopedia entry on this group, he is definitely looking at Lawrie and da Costa. Obviously Macoy has no real clue of how the cults of Dionysus worked, and just assumes the Dionysiac Artists were priests of the cults of Dionysus. Macoy is also the first to call them the "Dionysiac Architects." Where Robison, Lawrie, and da Costa claim they were architects and builders, they continued to refer to them at the Dionysiacs or Dionysiac Artificers. Macoy is the one who decides to rebrand them as the Dionysiac Architects.

Albert Mackey largely follows Macoy and Lawrie, especially in calling them the Dionysiac Architects and claiming they were priests of Dionysus. Mackey, for all that his encyclopedic entry is derivative of previous writers. However, Mackey makes an audacious claim when Hiram of Tyre sends these architects to Solomon to help build the Temple, Solomon ordered the Dionysiac Architects to communicate their mysteries to the Israelites, and vice versa. The union of their mysteries would "naturally" evolve into modern day Freemasonry and the legend of Hiram Abif's death and the creation of a monument to him. It is a wild invention of Mackey's, but curiously he then admits it is highly speculative and that if he is wrong about this, then it is "[George] Oliver" and Lawrie's fault:

The latter part of this statement is, it is admitted, a mere speculation, but one that has met the approval of Lawrie, Oliver, and our best writers."

Lawrie likely had been dead for two decades at this point. Oliver had been dead for over a decade when Mackey published his Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry. Macoy was still alive. The point being, Mackey presents his claim as if he had run it past these guys, though they had been dead longer than the date it is presumed he began composing his encyclopedia. So the other way of viewing his statement is that he is relying on the authority of the information they provide in their works to support his claim. Thus, if he is wrong, then it is their fault for making him think this bogus claim could be true. Mackey even appears hesitant to support his own entry on the Dionysiac Architects in his encyclopedia, but he stands by his claims on little more evidence than the theory of their existence and connection to Freemasonry is not so absurd as to not be completely false unto itself:

"Although this connection between the Dionysian Architects and the builders of King Solomon may not be supported by documentary evidence, the traditional theory is at least plausible, and offers nothing which is either absurd or impossible. If accepted, it supplies the necessary link which connects the Pagan and Jewish mysteries."

Mackey certainly had a way with words, and with these words he is trying to alleviate himself of any responsibility of disseminating and proposing bullshit. Spreading bullshit is exactly what he does.

One other thing Mackey does that sets up another line of falsehoods to be propagated by future authors, is where previous writers have stated that the Dionysiac Architects had secret words and signs as modes of recognition amongst its members, much like Freemasons have, Mackey especially states that they had a "universal language." It is an odd turn of phrase, and based on context he certainly means secret words and signs of recognition, but the next author in the chain of corruption, John Weisse, took this "universal language" to a new level. It is my conjecture that Mackey's term "universal language" led Weisse to claim that the Dionysiac Architects had "intercommunications all over the known world."

There are other Masonic writers that mention or discuss the Dionysiac Architects, though they do not appear to have much impact or consequence. Most their material is derivative, and on further inspection are absolutely a third or fourth generation corruption of the original source material in a bad game of scholastic telephone. Henry Bromwell is an interesting one, because as far as I am aware, he is the first to state that Hiram Abif was not only a member of the Dionysiac Architects, but also their Grand Master.

There are some comical moments of corruption, such as Weisse's attempt to transcribe some Greek, namely γυνοικιαι which he claims means "connected houses." This is a corruption of what Mackey attempts to transcribe, namely συνοικίαι which he claims was the word for "lodge" (the word he is looking for is οίκημα). It looks like Mackey was actually trying to transcribe some Greek provided by Lawrie, but it does not appear that Mackey actually knew Greek, or he knew enough to get himself into trouble, and so provides some bastardized word of no certain meaning. I do not know any forms of ancient Greek, so I myself may not even know what I am talking about.

We can skip over Mackenzie's Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia and Moses Redding's Illustrated History of Freemasonry, as I cannot get access to Mackenzie's work at the moment, and Redding's entry on the Dionysiac Architects is what one would expect from a source that is pulling from three or four generations of the telephone game.

We finally arrive at Manly P. Hall. The first entry in Hall's Secret Teachings of All Ages, he clearly heard about these Dionysiac Architects or read a small entry somewhere in another source. He appears suspicious of any claims about this group, and so what he writes is hesitant and humble. He uses terms like "supposedly" and "probably." Over the course of Hall composing this tome, he appears to have read more on the Dionysiac Artists-Architects. So in his last entry on them, he writes extensively and restates things from earlier with absolute certainty. One must wonder if he even reread or proofed his own book, because one would expect him to have modified his first entry to reflect the certainty he hold much later in the tome.

It is difficult to take Hall seriously, and not just because he makes countless unsubstantiated claims. He is less credible because he speaks at length and with immense certainty on the great secrets of Freemasonry, when he himself would not become a Freemason until twenty-five years after the publication of Secret Teachings. Further, and one particular reason I reserve suspicion for Hall, is that he started his career on Wall Street. He states that the materialism of working on Wall Street, as well as the disastrous outcome of the Great Depression, is why he turned to seeking spiritual things (see the Preface of the Diamond Jubilee Edition of Secret Teachings). The fact that the text sold out before it was ever even off the printing press, and the fact that he had all the funding he needed from investors and people willing to own the book by subscription before printing, tells me that he was a really good salesman with a silver tongue. Subscriptions for the book in 1928 was $15.00 at sign-up, and four payments of $15.00, for a total of $75.00. That is over $1000 in 2021. How does that not sound like a scam? The poor scholarship and the esoteric verbal masturbation that plagues the text tells me this work was more of a marketing scheme. Unlike many esoteric and occult writers throughout history, Hall did very well in making a lot of money off of his publications, and had secured for himself a hell of reputation that would last decades, and probably centuries.

In the latter portion of Secret Teachings in which Hall discusses the Dionysiac Architects is flooded with esoteric mumbo-jumbo, garbled logic, and ahistoical confabulations. It really is not necessary to detail everything he says about them, as all of that can be read in my previous post on the subject. What is essential to realize is that the Dionysiac Artists had taken on a life of their own, and Hall is largely responsible for disseminating the greatest amount of falsehoods about the group. In examining what Hall writes about them and looking back at Strabo, Aulus Gellius, Chishull, and Chandler, it becomes abundantly obvious that by time we get to Hall we are so far removed from any truths about the group. And yet Hall claims he is presenting the great secrets of history. It is a clever sales tactic.

There is a huge gap in history from Strabo and Aulus Gellius to Chishull, over 1600 years. Yet in the two hundred years after Chishull's translations of various stone fragments throughout Greek and Turkey, the Dionysiac Artists had transformed into something else entirely. They were once regarded as an immoral, drunken, traveling band of entertainers that were potentially corrupting to the youth, and were transformed into a fraternity of architects and builders exercising high morals and charity. It is such a bizarre transformation. But at the heart of it, we are looking at something from the ancient world that Freemasons sought to mold into an image that fit their belief that the Masonic Fraternity is far older than it actually is.