Any student of Classical architecture or simply someone who has perused Vitruvius is familiar with the anthropomorphic associations of the Orders. According to Vitruvius the Doric Order is a robust male warrior, the Ionic Order a mature matron, and the Corinthian a young female. But the associations between the Orders and various things become as diverse, convoluted, and arbitrary as those strange associations made between planets, days of the week, metals, plants, minerals, and the likes found in alchemy and magic and other esoteric arts. John Shute associates the Orders with various Greek deities (seen in image above): the Doric is Herakles, Ionic Hera, and Corinthian Aphrodite. H.V. de Vries associated the Orders with times of the day (e.g. Composite Order - sunrise; Corinthian - morning, et cetera). Vredeman de Vries (unrelated to H.V. de Vries as far as I can tell) associated the Orders with the five sense (e.g. Doric - hearing; Ionic - smelling; Corinthian - tasting; et cetera). George Hersey demonstrates in depth how most of the elements of the Doric Order are sacrificial in symbolism and the Ionic ceremonial in nature. Then comes the associations made between the Orders and plants: the various myths of the primitive hut (save for Alberti's version) claim that the idea of the column came from trees, and even the Corinthian Order resembles in a tree; Egyptian columns were often modeled after lotus and papyrus plants. The associations and connections keep piling up, and some authors will make associations that conflict with another author — just like in alchemy — and thus confuse the whole matter to the point of futility in the search for solidarity.

But probably the one association between the Orders themselves and some other idea that isn't often discussed is the use of the Orders in nationality and race. They are called the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian Orders after all — the later being a city rather than a region. Sometime around the 18th Century countries began to develop their own "Orders" of architecture to express ideals of nationality: James Adam (brother of Robert Adam) developed the British Order; Benjamin Latrobe developed the American Order (several, actually), one of which was later modified by Alexander Jackson Davis; Edwin Lutyens developed a Delhi Order for the British Empire in India; there were a variety of French Orders, with one of the first being developed by Claude Perrault; et cetera. Certainly there is an idea of nationality and politics in architecture, and especially in the forms it takes — countries have been using architecture for political ends for century, take for instance Mussolini and Hitler; the British also made good use of architecture for the exhibition of political power in India; Louis Kahn contributed to the political power of architecture in Dhaka, Bangladesh; even King Solomon's Temple was a political move, as well as Herod's motion to rebuild it; and so forth — it stands to reason that the ancient Greeks would be no different; and they were not any different. I believe it was Philip Johnson who once say, "All architecture is politics; politics is sometimes architectural" (I don't know if he actually said that; a professor once told me that — whatever the case may be, it's worth reiterating here).

Map of the dialects of ancient Greece and their cities and territories

Up until the Greco-Persian Wars architectural styles throughout the Hellenic world did not mix very much — actually we see practically no examples of Ionic architecture in mainland Greece, nor Dorian architecture in eastern Greece (western coast of modern day Turkey — in fact it was the opinion of many Dorians in Archaic and Classical Greece that the Ionians were not even actual Greeks). The mainland Greeks tended to building relatively austere and robust limestone structures, while the Ionians and Aeolians tended to build more slender, daintier and ornate marble structures. Before the Persian conquest of Greece and Turkey there was not a very strong sense of opposition in nationality among various Hellenic cultures: Dorians didn't really hate Boeotians or Ionians because they were not Doric, rather being a Dorian or Aeolian was a matter of pride in one's culture, dialect, and art — the pride was much the same as Northerners and Southerners pre-American Civil War, in which it was a pride of one's culture, and with little animosity or aggression just because the other has a different dialect. The animosity between Dorians and Ionians really arises when the Persians began to invade the Aegean Sea area: the Dorians resisted the Persians while the Ionians surrendered.

The resistance of the Aegean Greeks against Persian conquest begins in the funding of the Athenian Empire in Attica, which was primarily a fund for the expansion and maintenance of naval fleets in the Aegean Sea. Like any political fund, these funds were not always used for their primary purpose. Out of the fund began a series of building projects that included the the rebuilding of the Parthenon and other monuments in the mid-5th Century BCE. This is just about the time period in which Ionic architectural styles begin to spring up in mainland Greece. Turn back the clocks about fifty years: four decades after the Ionians surrendered to the Persians several Ionic city-states revolted against Persian rule beginning in 499 BCE; the revolt was started by Miletus and Aristagoras, two native Ionian tyrants who failed to conquer Naxos, and, fearing being removed as rulers, revolted against the Persian king, Darius. The revolt ended in 495 BCE, but the spirit of ending Persian rule in the Aegean sea persisted. In 480 BCE the Persians were defeated at the battle of Salamis, and retreated from mainland Greece back to Asia Minor. Subsequent naval battles within the next year — such as those at Plataea (Boeotia) and Mycale (Ionia) — against the Persians eventually liberated much of Ionia from Persian rule (most especially the battle of Mycale). Much of these naval victories could not have been possible without the alliance of Greek city-states and the funding of Athenian fleets.

Shortly after the liberation of Ionia from the Persians the Athenians built the Stoa of the Athenians next to the Temple of Apollo in Delphi (Boeotia), which was built using the Ionic Order. This stoa was dedicated by the Athenians for their naval victory against the Persians. This stoa really being the first real example of the Ionic style in mainland Greece, it is reasonable to presume there was a political motive behind the use of the Ionic; quite probable a Panhellenic political ideal (i.e. an alliance or gesture of friendship of the Dorians with the Ionians), and at the very least a commemoration of the the liberation of Ionia with Athenian aid. Within a decade of the Athenian Stoa in Delphi another Ionic building was erected in Attica: that of the Temple of Athena in Sunium — it has been speculated that the L-shaped Ionic portico that faces the Aegean sea may haven been a friendly gesture to seafaring Ionians visiting Attica. Aside from these two structures most Athenian building projects remained in the native Doric style. It would be a few more decades before Athenians began using the Ionic Order again, and when they did it was used for interior purposes.

Temple of Athena at Sunium (left) and Stoa of the Athenians at Delphi (right)

The ambition of a Panhellenic alliance really gains notoriety with Pericles (5th Century BCE Athenian statesman — often called the "first Athenian citizen"), and with the Panhellenic alliance comes the move for Athens to be the center. According to Thucydides Pericles wished Athens to be the "school for the whole of Greece." He wished Athens to be a perfect cultural union of virile Dorian ideals and relaxed, luxurious Ionian ideals: "We [Athenians] pass our lives in a relaxed way and, yet, are no less ready to face equal danger [to that of the Spartans]... [we] love beauty without extravagance, and love wisdom but without softness" (Thucydides, History, II.39-40). As such, new Athenian building projects that utilized both the Doric and Ionic Orders would then typically use the Doric on the exterior to symbolize masculinity (i.e. outside is where masculine activities are done, such as exercising, fighting, building, et cetera — Spartans and other Doric warrior cultures dressed in an austere fashion or wore armor), and the Ionic on the interior to symbolize femininity (i.e. activities performed inside, such as eating, philosophizing, and other luxuries were regarded as feminine — Ionians, followed by Athenians, wore robes and luxuriant clothing).

Two of the first major Athenian building projects to utilize both the Doric and Ionic Orders were the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens and the Temple of Apollo in Bassae (Arcadia); both were built around the same time period, and both are attributed to Pericles' beloved architect, Ictinus. The Parthenon uses the Doric Order on the exterior peristyle, a two-story Doric interior peristyle in the cella, and four Ionic columns in the rear cella (obvious not for structural purposes given the span of the main cella). The rear Ionic chamber of the Parthenon was likely used as a treasury. It is also interesting to note that one of the arms of Athena in the Parthenon was supported by a small Corinthian column.

The Temple of Apollo at Bassae is an enigmatic structure unto itself. Its design and construction preceding the Parthenon (according to Pausanias the temple was built c. 421 BCE, but modern scholars date it around 450 BCE — Parthenon built c. 438 BCE), it is actually the first structure to utilize both the Doric and Ionic Orders, and includes the birth of the third: that of the Corinthian Order. There are examples of what are the so-called proto-Corinthian columns, namely at the Treasury of Massilia in Delphi (c. 530 BCE) — these proto-Corinthian capitals could be called Aeolian capitals, since Massilia was an Aeolian-Ionian city. (I personally hesitate to call these proto-"Corinthian" simply because they do bear some similarities with proto-Ionic capitals — commonly called Aeolian capitals — with their leafy volutes; dating around the 6th and 7th Century in Turkey). But Bassae is really regarded as possessing the first example of the Corinthian Order. It is a single column (called an axial column) flanked by two Ionic columns at the end of the cella — it actually has more prominence in the cella than the statue of Apollo. The architrave above the Corinthian column is a continuation of the surrounding Ionic peristyle.

Furthermore concerning Ionian influence in western Greece can be found at Bassae: a bronze manumission was foun at the site (dating to the 4th Century BCE) that use the Arcadian alphabet, but with several alterations, namely utilizing Ionian letters (see Cooper Temple of Apollo, chapter II).

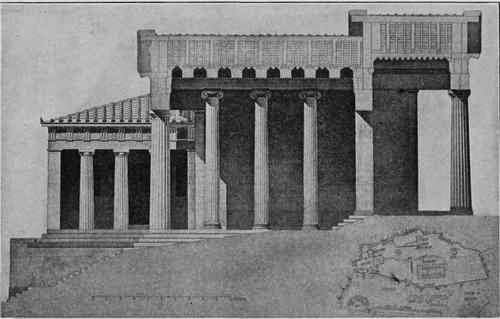

Sectional views of the Parthenon in Athens (left) and interior perspective of the Temple of Apollo at Bassae (right)

It was Vitruvius who esoterically said that the Corinthian was born from the "union" (literally procreation) of the Doric and Ionic (De Architectura, IV.1.3). It is difficult to know whether or not Vitruvius had the Temple at Bassae in mind when he wrote that, for he never actually mentioned the Temple at Bassae.

There is a third structure that was built a couple of decades later that utilizes the Doric and Ionic Orders: the Propylaea, which is the structure that provides the entrance onto the Acropolis. On the outside stands the Doric Order, but once under the canopy the columns become Ionic, and on the other side on the Acropolis the columns are Doric again. There are two reasons for doing this: one, masculinity goes on the outside; and two, there is a change in elevation, so the Doric on the on top of the Acropolis is several feet above the Doric Order at the entrance (hence the two pediments when viewed in elevation) — the Ionics align with the upper Doric columns, thus providing a rather clever segue between the two elevations.

Propylaea longitudinal section (note the height variation)

Well, Pericles died in 429 BCE, and the ambition of a Doria-Ionic alliance began to deteriorate. Athens became increasingly dependent on the Ionians, and their architecture would continue to reflect a strong Ionian alliance with alienation towards to Dorians. As such, many Athenian building projects began to use the Ionic and Corinthian Orders without the Doric. Firstly, there is the Temple of Athena Nike, a purely Ionic temple, which is directly next to the Propylaea and figures prominently when entering the Acropolis. Then comes the Erechtheion, which seems to change everything.

The Erechtheion is primarily Ionic in style the exception of the Porch of the Maidens, which uses one of the most famous examples of Caryatids (columns sculpted like humans) — the Caryatids (as Vitruvius so named them) are not the first example of anthropomorphic columns: the Treasuries of Siphnos and Cnidus at Delphi also used Caryatids on their porticoes. What makes the Erechtheion the prime example of Athens' alienation from the rest of Doria and resting solely on their Ionian allies is the myth of Erechtheus that was weaved and perpetuated by Euripides in his play Ion (and probably as well as in a lost play of his, Erechtheus): Erechtheus was an actual king of Athens, and is mentioned in the Iliad, but became a mythic character, so much so that it is hard to differentiate between the actual king and his legendary self. Euripides wrote Ion around 414 BCE, and mythologizes how King Erechtheus fathered Ion, who would go on to colonize and build Ionia.

Erechtheion reconstruction

Plays and works of poetry were rarely written in ancient times without political motive, either by a king or the author trying to become favorable with the king (Vitruvius did this with Caesar Augustus, as is evident in the prefaces of De Architectura) — take for instance Virgil's The Aeneid, which mythologizes how Aeneas fled burning Troy, eventually ended up in Latinum, and Julius Caesar and Augustus were progeny of Aeneas, whose mother was Venus. It is highly probably that the Erechtheion and Ion are testaments to Athens' loss of alliance with the Dorians and an attempt to strength their relation to their Ionian friends; even if it meant mythologizing that the two nations were actually kin.

On the other hand we have the Dorians, who continued to use their robust Doric Order for sometime until after the death of Pericles, who then began to utilize the Corinthian in their interiors instead of the Ionic. This is probably a shunning of the Ionians who had over a century before hand surrendered like cowards to the Persians. The anatomy and proportions of the Corinthian Order should be indicative of this: according to Vitruvius the Corinthian is simply the Ionic column in which the Ionic capital has been removed and the taller Corinthian capital has been placed on top (note that at the Temple in Bassae the Corinthian column is slightly thinner than the Ionics, possibly to account for the slightly taller Corinthian proportions). In a way the Dorians simply removed those much hated Ionians' capital and replaced the capital with one of their own — they kept the fluted shaft and the Attic base, but used a feminine capital that was Dorian. Corinth is after all a Dorian city neighboring fairly close to Attica on the Peloponnesian Peninsula.

As to why that Order is called Corinthian is a bit of a mystery, as it was not developed in Corinth, but Arcadia. There are two possibilities: one, that the slender proportions and dainty ornament of the Order reminded the Greeks of a young girl (the anthropomorphic argument), and so they called it kore (κόρη), "maiden", which in turn came to refer to Corinth (root word: kore), a city known for its sacred prostitutes; the other reason being that the first Corinthian column, i.e. at Bassae, was of such intricate and delicate design that it was more than likely marble covered in bronze ornamentation (we don't know the exact properties of it because it was lost while in Zakynthos during the 1953 earthquake, all we have are 19th Century archaeology drawings) — the bronze ornamentation may have reminded the Dorians of Corinth, which was known for its beautiful and well-crafted bronze vessels. That's about all Corinth was known for: sacred prostitutes to Aphrodite and bronze works.

In a way, the use of the Corinthian instead of the Ionic could be seen not so much as a shunning of the Ionians, but as introducing the newly developed, pretty, leafy Corinthian column, and to avoid any racial or political overtones. At the same time it seems to have racial overtones.

Thus we find Dorian architecture in the late 5th Century through the late 4th Century BCE using the Corinthian instead of Ionic. The tholos (a round building) sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidauros (c. 360 BCE) used the Doric Order on the exterior peristyle and Corinthian on the interior peristyle (this use of the orders may have esoteric overtones). Similarly in Epidauros is the Temple of Artemis (c. 330 BCE), which also has a Doric portico and interior peristyle of Corinthian columns. Those are really the two major Dorian-Corinthian structures. For the most part the Dorians kept with their robust Doric columns.

Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidauros

But even with the Dorian animosity towards Ionia, it seems that nearly two centuries after the Greco-Persian Wars that such animosity might have died down. On the other side of the Peloponnesian Peninsula in Olympia the tholos Philippeion utilizes the Ionic Order on the exterior peristyle and the Corinthian on the interior. But then again, even in Epidauros the Temple of Aphrodite (c. 320 BCE) uses the Ionic Order on the portico and a Corinthian peristyle on the interior.

It is really around this time that the Orders begin to be used more for aesthetics and possible esoteric-symbolic purposes (such as the anthropomorphic reason). It seems reasonable that after a few hundred years with these architectural styles that the ancient Greeks would begin to mythologize them and make esoteric-symbolic associations with them. This becomes evident with certain Corinthian monuments at Delphi, such as the acanthus column.

Whatever the case, it should be clear that the Orders did not always have esoteric associations, though those associations certainly must have existed, but were far more subtle than the racial associations with the Orders. These racial and political overtones with the Orders were used in the decades following the Greco-Persian Wars, and symbolized alliances, as well as alienation with certain Hellenic races.

One thing is for certain, and that is that the great Greek Classical Era is significant architecturally for the refining, development, and experimental use of the Orders; but as can be seen, this experimentation was largely politically motivated, rather than aesthetic. We may not have those great architectural works such as the Parthenon, the Temple of Apollo at Bassae (a personal favorite of mine), the Erechtheion, the Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidauros, the Athenian Stoa at Delphi, the Propylaea, and the likes — at least not as we known them today — were it not for such racial and political tension that occurred in Greece during the aftermath of the Greco-Persian War.

Further reading:

Herodotus. The Histories.

Thucydides. The History of the Peloponnesian War.

Pausanias. Description of Greece.

Onians, John. Bearers of Meaning. Princeton University Press. 1988. <<Refer to Chapter 1 for political and racial uses of the Orders>>

Rykwert, Joseph. The Dancing Column. The MIT Press. 1996.

Cooper, Frederick A. The Temple of Apollo at Bassai. Garland Publishing, Inc. 1978.

-121329699737467.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment